The Shapeshifter: Character and Role-Play Through the Lens of Theater

- miloduclayan

- Sep 11, 2025

- 7 min read

Updated: Sep 20, 2025

This essay contains very minor spoilers for Disco Elysium.

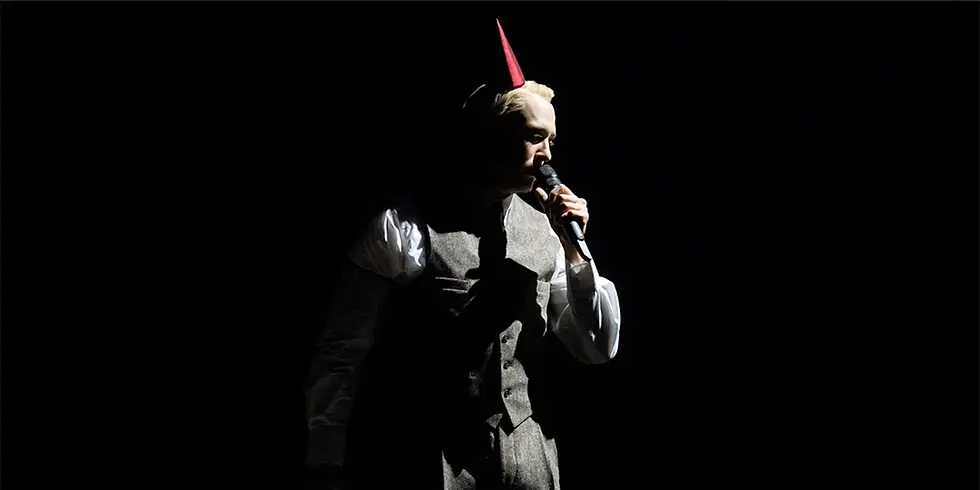

We open on a spotlight, center stage. Orville Peck, dressed in the Emcee's new years garb, strikes a contorted pose, audibly framed by a crash of cymbals. He has a smile stretched over his face.

Cabaret's Emcee is one of the most iconic characters in theater. I've watched plenty of different takes on him, from Joel Grey's seminal Broadway run and later film adaptation, to Alan Cumming's renowned revival performance, and now, of course, Orville Peck's run in the West End-directed version.

The Emcee is obviously not the only character that's been played by different actors over and over, but he is one of the few characters that seems to have no end to the number of iconic and noticeably different takes. I think the answer to why lies in who the character is.

In Cabaret, the Emcee acts as a kind of meta-character. He does exist in the world of the play, of course, but for the sake of the show he's mostly representational. He exists to translate the story of Cabaret for the audience, as a lens with which to view the rest of the show. Because of this, every time someone new takes on the mantle, they get to choose how to shift the lens. Alan Cumming played someone trapped in their own world, watching it fall apart around them but completely unable to stop it. Orville Peck, in an interview with Playbill, explains his take differently: "The Emcee’s job is to win people over and then betray them". Orville Peck's Emcee is a villain, who shapeshifts to the side of the winner, sacrificing his internal world for the sake of survival, and willing to sacrifice anyone else who threatens it, too.

The most interesting thing to me is that at its core, the script of Cabaret — or any stage production for that matter — functions like a pre-generated character sheet. The sheet simply defines exactly what words the Emcee says and generally the context in which he says them. Everything else is fair game for the director and actor to decide.

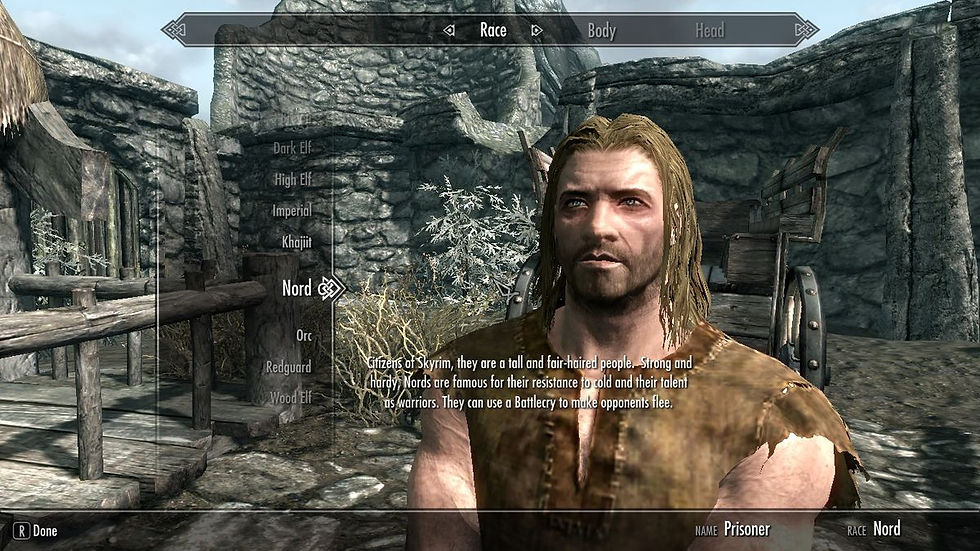

There's an age-old discourse in the RPG community about whether player characters should be pre-generated or blank slates. Games in the style of The Elder Scrolls and Dragon Age allow players to customize their characters in almost any way, which unfortunately often leads to less focused and impactful narratives. It's particularly hard to involve the player character in a story when the writers have little to no idea who the player character will be. The other problem here is that it's very hard to get players to willingly fail.

I was recently watching Brandon Sanderson's lecture on characters, in which he mentiones that a good character will generally have one thing they're reliably good at, one thing they're reliably bad at, and one thing they're going to improve over the course of the story. One of the problems we run into often with blank slate-style RPG video games is that the player character tends to have no real character arc. They can't have a character arc when players will so rarely choose to be bad at things (especially when save-scumming is an option), so they never have a chance to develop in a way that feels narratively meaningful.

This is often mitigated in tabletop role-playing games, because the benefit of a game master is that the story writer is present to work with you as you build your character. The problem becomes more apparent when playing through pre-written modules that cannot provide interesting space for every possible character, in a similar way to RPG video games.

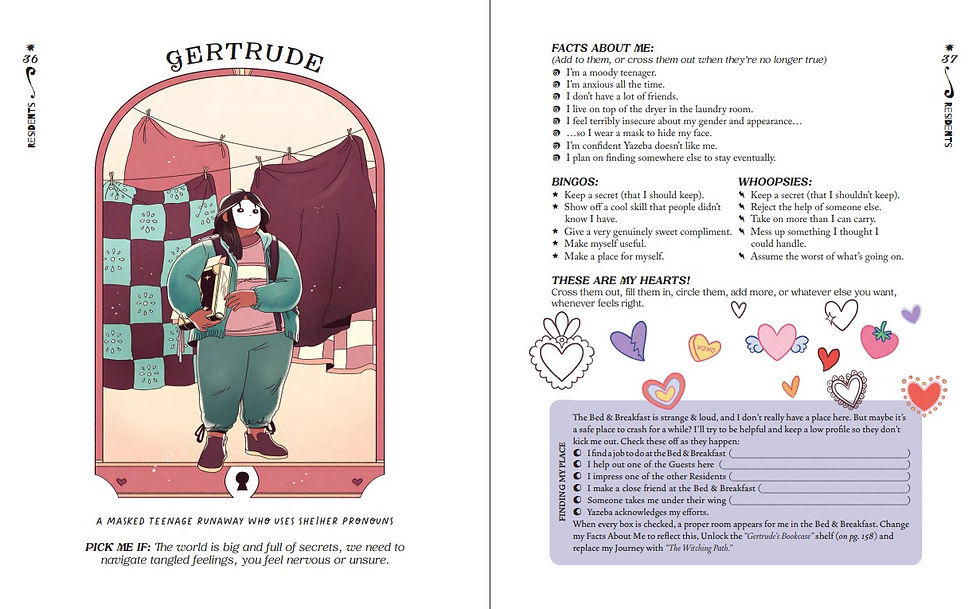

Thus, enter the pre-generated character sheet. In RPG video games like Disco Elysium and Omori, or TTRPGs like Yazeba's Bed and Breakfast or Alice is Missing. In these games, the outlines of the character are pre-defined, allowing them to be better slotted into the writer's world. Pre-generated characters also allow players to dive deeper into narratives and spaces that they likely would never have even touched if they were given total freedom. Take, for example, this set of facts from the character sheet for Gertrude, one of the main characters of Yazeba's:

FACTS ABOUT ME:

(Add to them, or cross them out when they’re no longer true)

+ I’m a moody teenager.

+ I’m anxious all the time.

+ I don’t have a lot of friends.

+ I live on top of the dryer in the laundry room.

+ I feel terribly insecure about my gender and appearance…

+ …so I wear a mask to hide my face.

+ I’m confident Yazeba doesn’t like me.

+ I plan on finding somewhere else to stay eventually.

These outline a general frame for the character, including threads for interesting flaws, personality traits, and goals for players to pull on. By establishing them, the game designer has the ability to frame the rest of the game around these character traits, building a framework that allows for far more interesting characters in a much more accessible way.

In a mind-boggling parallel, Disco Elysium takes almost the exact same approach. Here's a quote from one of Harry's Thought Cabinet thoughts, "Rigorous Self-Critique":

Here it is. Hard facts from the man you are. You once jerked off in the locker room and were caught. You held a young woman by the arm and kept her in your apartment for 20 minutes against her will. That's right, these are not flights of fancy. These are *real deeds*, Harry, emerging from the darkness of your past. You tried shooting a fleeing suspect in the foot but hit him in the pelvis, crippling him for life. And above all, you let life defeat you.

Although the truths that these two characters are given are very different, they function in very similar ways. Each established element of the character gives the players something to push against narratively, instead of leaving them floundering.

Importantly, both games also allow room for the characters to grow and change over time, making space for that character development so importantly pointed out by Sanderson.

Live theater presents something interesting we can learn from, to this end. As I said before, it helps if we imagine the script as the "facts" of a pregenerated character sheet, and the actors as the players of this strange sort of Actual Play. Despite every word the character says being set in stone, each actor is nevertheless able to bring new meaning to them, changing the experience of the show (read: game) because of how they choose to interpret that character's truths.

The visibility of this can also be seen through shows that are so old they've been repeated more times than can even be counted. I'm talking Romeo and Juliet.

It's generally accepted that when adapting Shakespeare you should keep as much of the original text the same as possible. Again, facts on a character sheet create interesting limitations and allow the rest of the story to be built around it. But the maintenance of general language and plot hasn't seemed to stop anyone from changing the meaning of the story.

I'm sure Shakespeare could never have forseen Baz Luhrmann's wild 1996 adaptation, but my most recent favorite version was the Broadway run starring Kit Connor and Rachel Zegler, directed by Sam Gold.

The trick with Romeo and Juliet is that everybody in the world has already seen it. Not only are the actors and director pushing against the script, they're also pushing against the cultural expectations of who these characters are and how they should act. Push too hard, and people will be put off. Don't push enough, and nobody will be interested.

One particular standout performance comes from Sola Fadiran, who plays both Lord and Lady Capulet. Lord Capulet's monologue in Act 3 Scene 5 is perhaps the only time in any version of Romeo and Juliet I've seen where I have felt genuinely intimidated by the character. This level of nuanced emotion from Capulet ripples through the whole show, and recontextualized my interpretation of the entire plot.

Pre-generated characters are often associated with quick, simple, and shallow outputs. This is especially prevalent in the Dungeons & Dragons space, where the foundational system of the game is to have a blank slate. Of course, if you randomly generated a character in Skyrim, it would probably be pretty boring - not only does it remove the fun parts of fully customizable character creation, it also doesn't win back the benfits of pre-gens. Unfortunately this sentiment has leeched out into other parts of the RPG space, where I don't think it's particularly warranted. Again, in live theater, actors don't just benefit from the established characters, they thrive off of them. You don't get a great performance like Orville Peck's or Alan Cummings' without great writing from Kander, Ebb, and Masteroff.

These thoughts about pregenerated characters come at a time when I'm actively developing a TTRPG, and the idea of using pregenerated characters for it is one I've started exploring. For me, it provides the benefit of making inter-personal conflicts without asking players to write them themselves, and potentially (intentionally or unintentionally) make the conflicts weaker than I want them to be. It also helps resolve some issues of character motivation, by pre-establishing things that are meaningful to each, and providing both a frame for players to play within (and fight against), and giving them threads to pull on if they so choose.

The idea of live theater functioning as a game, and a way for us to understand how to adapt established rules about a character, was also partially inspired by Jay Dragon's recent Expressionist Games Manifesto.

Rules provide us a way of framing stories, and what are scripts, character facts, and established backstories if not additional rules for us to challenge?

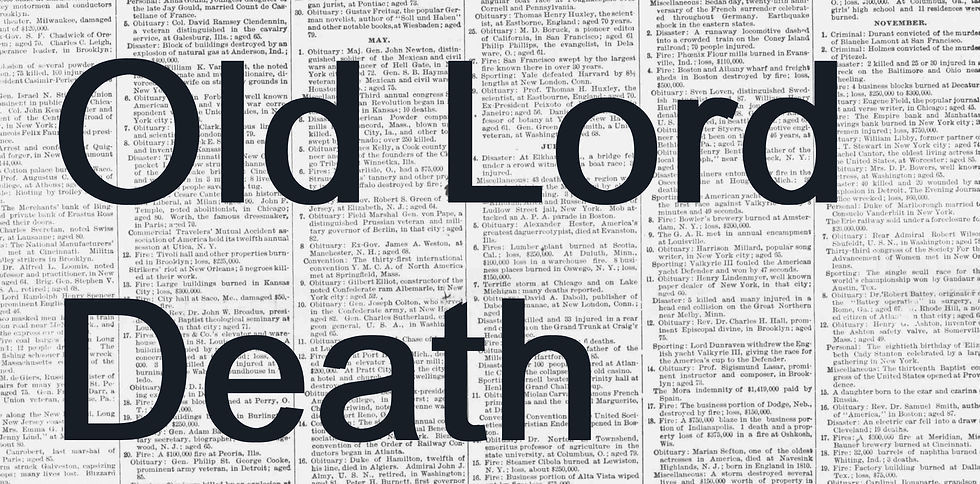

As an additional experiment to go along with this essay, I also decided to try and make a game using an unconventional form of character sheet. This is a game where you play as a spirit, and your character sheet is a real archived obituary. See how this character exists not as the person they were, but as only the truths the people around them chose to remember them by.

You can play the game at this link: https://antennasunite.itch.io/old-lord-death

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

There have recently been quite a few random thoughts floating around about games and live theater. This article grew out of the seeds those thoughts planted. Some of these include a LinkedIn post by Manny Hagopian, a conversation I had with Shannon Chou, discussions in Jay Dragon's patreon community discord, and a Bluesky post that I saw but cannot for the life of me find again.

Comments